Italian Canadian Women Gain Employment during War Periods

Men on the battle front, fighting for their lives and for their nations, are the images often depicted of the two World Wars. Forgotten are the women, who were left on the home front, helping to win the war through their care for their family while simultaneously working to support them. Rosie the Riveter became this symbol for all female war workers during WWII. However, Rosie’s story is not an accurate representation of all women’s stories, especially the stories of immigrant women. Thus, this research has a purpose to share the stories, the participation, and the contributions of Italian-Canadian women in the workforce during periods of war.

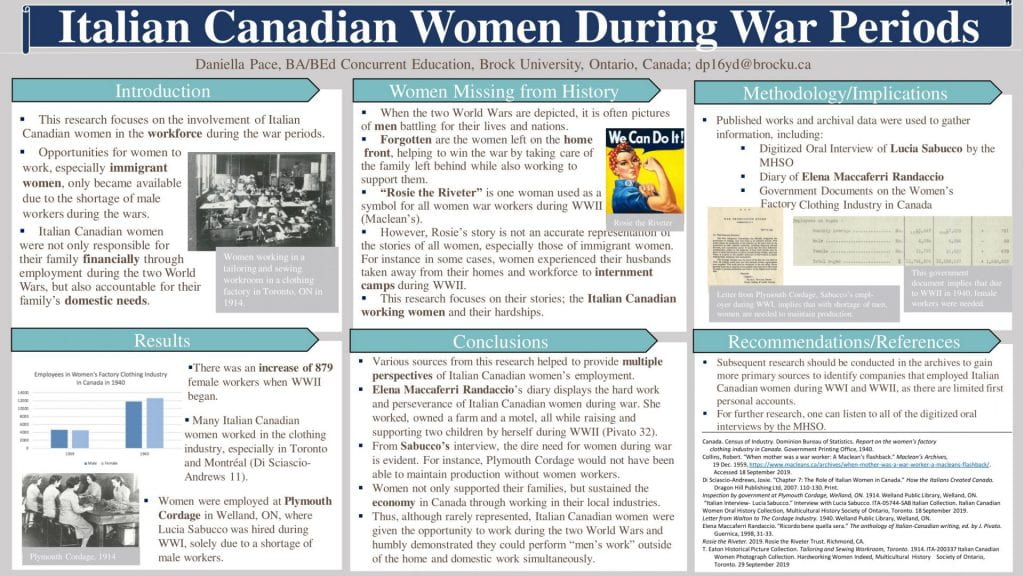

The opportunities for employment only became available to women, especially immigrant women, due to a shortage of male workers in war time. During war periods, Italian Canadian women were not only responsible for their family financially through employment, but also were accountable for their family’s domestic needs. The methodology in this research includes the accumulation of information through both published works and archival data. The first archival piece is a digitized oral interview with Lucia , created by the Multicultural Heritage Society of Ontario (MHSO). In her interview, Sabucco discusses the opportunities she was given during WWI to be employed at Plymouth Cordage in Welland, ON. The letter from Plymouth Cordage headquarters, stating that during war production must increase even with the shortage of male workers, displays the dire need for female workers to maintain and even increase the company’s production. The diary of Elena Maccaferri Randaccio provides a first-person account of an Italian Canadian woman in the workplace. Her story also demonstrates the employment that Italian immigrant women were forced to find (or create) in order to save their homes and provide for their families during World War II. She maintained the family farm and operated a motel with two children, while her husband was imprisoned in an internment camp in Canada. Further, archived government documents from the Dominion Bureau of Statistics concerning Women’s Factory Clothing Industry in Canada demonstrates that the number of female workers from 1939 to 1940 increased, implying that women’s employment rose with the dawn of the second world war.

The results of this research reveal an increase of 879 female workers in the Canadian clothing industry when WWII began. The graph visualizes this major increase in just one year. Additionally, the archival photograph from 1914 in this study reveals the increase in female workers during World War I at Plymouth Cordage, demonstrating that not only Lucia Sabucco was hired during a shortage of workers in war. In conclusion, the hard work and perseverance of Italian Canadian women during war periods is evident through these women’s stories—the voice of Sabucco and the writings of Randaccio. So too is the reliance of women in the workforce to sustain the economy in Canada through their employment in local industries demonstrated in archived government statistics from the early 1900s to 1940. Thus, although rarely represented in studies, Italian-Canadian women were given the opportunity to work during the two World Wars and humbly demonstrated that they could perform work classified as “men’s work,” while simultaneously continuing “women’s work”—their domestic work— and caring for their children.

Daniella Pace,

Brock University, 2019